The extremely steep scree slopes didn’t alarm me. Neither did the ice in the drainages, the mud, or the incessant drizzle. What did have me a bit unsettled was simple math.

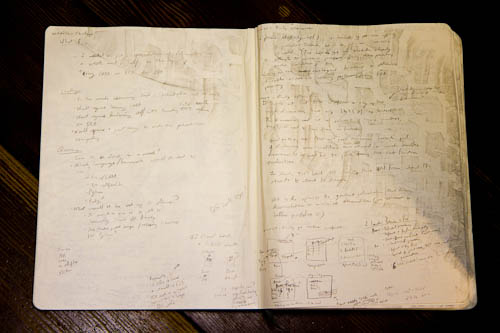

Tyler and I had crested the ridge at 5500 feet, the valley floor was at 3900 feet, and the horizontal distance between the two was about a mile. That implied an average grade of about 30%. However, even though the initial descent off the ridge had been rather hairy, perhaps a 60% grade, the overall path down the drainage felt nowhere near steep enough. We had a lot of vertical distance to drop without a lot of ground left to cover.

We worked our way down the drainage in a gap that was becoming increasingly narrow. It was cold, wet, and gray. We were looking forward to getting to the Toklat River valley and its gravel bar so that we could set up camp and dry out.

Soon, the rocks were so close together that we were walking in the creekbed itself; a slot canyon. I was in the lead, and Tyler was a half dozen yards behind me. I rounded a bend, and in that moment I saw where that missing elevation went. Ten feet in front of me, the ground dropped away and the water rushed over it. It was a waterfall. A bloody waterfall. I couldn’t believe it.

I crept to the edge to better assess the situation. The waterfall was at least 80 feet high. As we were in a narrow sheer-faced canyon, there were no routes around the waterfall. The rock alongside the fall was totally rotten and unclimbable. It might have been possible to climb down the fall itself, but that would have required technical climbing gear, which we lacked. An unprotected climb would have been suicide.

I backed away from the edge as Tyler came up behind me. I was a bit freaked and was shaking from adrenaline.

We talked it over briefly, but our options were limited. Neither of us relished the idea of regaining the 1000 vertical feet to go back over the ridge, especially considering the loose rock at the top of that route. Going down the waterfall was clearly out, too. We pulled out the topo map to consider our alternatives.

Another drainage a half mile to the north of the one we were in appeared to be viable. The trouble was that waterfalls are not usually marked on USGS quads. Another waterfall could have easily been hiding in that drainage; the map had provided no hints to the presence of the one we had already encountered.

The pass to that drainage was 700 feet above us and about a half-mile hike. I was still feeling a bit shaky as we turned around and began hiking back up.

At that pass, we stared into the next drainage. We had thought that coming down from the main ridge was a hairy descent, but that had nothing on our new challenge. The slope below us was easily 45 degrees — a 100% grade — and consisted of loose scree, dirt, and mud.

The rain continued to fall, further complicating the situation.

Gaiters were donned. (Twice for me. I always seem to put them on the wrong legs on my first attempt.)

We began our trek down the extremely steep, sketchy hill, half stepping and half sliding. Very slowly.

After quite a while, we made it to a slightly less extreme stream bed, which made the downclimb marginally easier.

The feet of altitude ticked away as we continued our descent. There were some short cascades in the stream, but those were easily managed. So too were a pair of small waterfalls, which we were able to skirt by traversing some steep talus. Things were going well.

We were just a few hundred feet off the floor when the rock again narrowed into a slot canyon. We crossed our fingers, but our luck ran out. We rounded a bend and saw… a waterfall. Another bloody waterfall. I couldn’t believe it.

Fortunately, that one was considerable shorter than the first at about 12 feet high. The rock was rotten again, but some of it appeared climbable, and attempting the descent did not seem likely to be fatal even if we cratered.

Tyler and I decided to commit.

I tossed my hiking pole to the base of the fall and began to downclimb the rock next to, but not in, the water stream. Everything went fine for the first few feet, but then what I had feared came to pass: my holds flaked off, and I fell.

I felt the rocks give away and myself grinding down the face.

Fortunately, it wasn’t a long fall, and I managed to land on my feet at the base, staggering back a bit. The rocks I had dislodged fell harmlessly around me. Tyler yelled down to me over the roar of water to see if I was OK.

A quick assessment showed some damaged gear, a sore chest, and a bleeding knee, but no bones broken or joints twisted. I stood there in shock for a couple of minutes.

It soon was Tyler’s turn. He wisely chose to climb down the fall itself, in the stream of water. The rock was better there, and my view from the base revealed many viable holds.

Still, the climb was not without risk, and from Tyler’s perspective most of the holds were invisible beneath the rushing white frothy water. That same water also did a fabulous job of totally drenching him. Whatever the rain had not found, the waterfall’s flow did.

Happily, Tyler made it down without incident. He had embraced the waterfall, and it had smiled upon him.

Tyler celebrates after climbing down a waterfall

Even better, the drainage opened up wide after that point, and we encountered no more major impediments. We successfully made it down to the Toklat River: Denali Backcountry Unit 10.

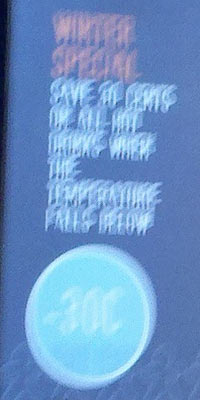

When we were getting out backpacking permit, the ranger hadn’t batted an eye at our proposed itinerary. However, when we later told people about our surprise at encountering waterfalls when going form Unit 11 to Unit 10, they almost universally smiled and nodded in amused understanding. It felt like we were the only people in the park who didn’t know that you’re not really supposed to go from Unit 11 to Unit 10 (at least not over the ridge). Interestingly, the Unit 10 description mentions the waterfalls and two other problems we would later have: encounters with bears and the difficulty of the pass from Unit 10 to Unit 12. It would seem that we overlooked those details. We learned the hard way.

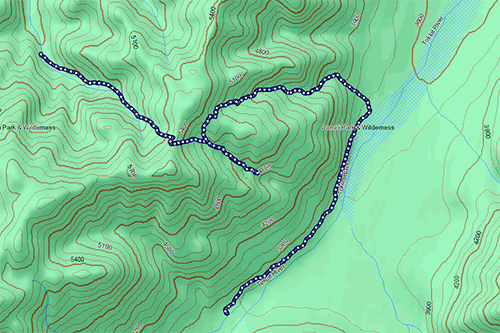

Our path that day, as recorded by my GPS. Note how the topo map doesn't really indicate the presence of a waterfall. (Click for larger annotated version)

The total distance was only 4 miles or so, but those were the most difficult 4 miles of backpacking I’ve ever done.

Recent Comments